Social, environmental, and economic consequences of integrating renewable energies in the electricity sector: a review

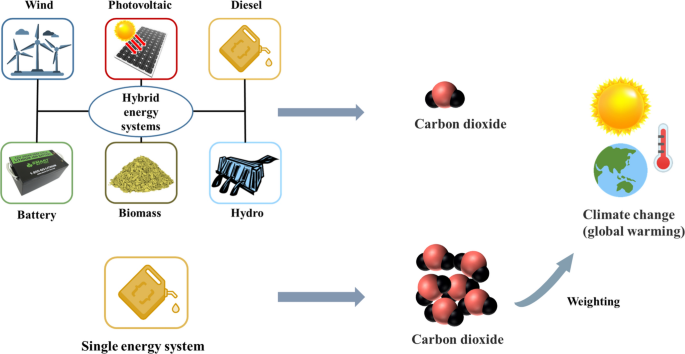

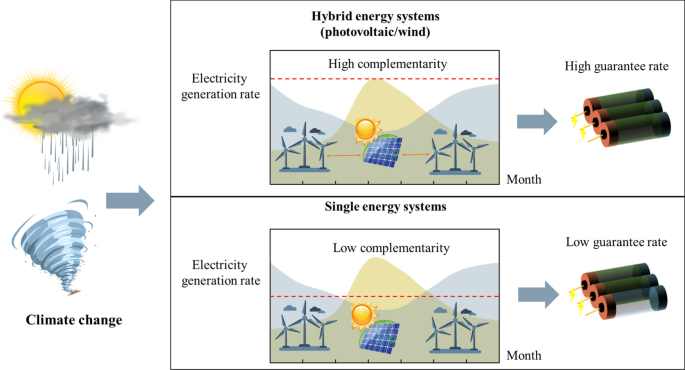

The global shift from a fossil fuel-based to an electrical-based society is commonly viewed as an ecological improvement. However, the electrical power industry is a major source of carbon dioxide emissions, and incorporating renewable energy can still negatively impact the environment. Despite rising research in renewable energy, the impact of renewable energy consumption on the environment is poorly known. Here, we review the integration of renewable energies into the electricity sector from social, environmental, and economic perspectives. We found that implementing solar photovoltaic, battery storage, wind, hydropower, and bioenergy can provide 504,000 jobs in 2030 and 4.18 million jobs in 2050. For desalinization, photovoltaic/wind/battery storage systems supported by a diesel generator can reduce the cost of water production by 69% and adverse environmental effects by 90%, compared to full fossil fuel systems. The potential of carbon emission reduction increases with the percentage of renewable energy sources utilized. The photovoltaic/wind/hydroelectric system is the most effective in addressing climate change, producing a 2.11–5.46% increase in power generation and a 3.74–71.61% guarantee in share ratios. Compared to single energy systems, hybrid energy systems are more reliable and better equipped to withstand the impacts of climate change on the power supply.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Opportunities and Challenges for 100% Renewable Energy

Chapter © 2022

Energy Conversion from Fossil Fuel to Renewable Energy

Chapter © 2023

Energy Conversion from Fossil Fuel to Renewable Energy

Chapter © 2023

Explore related subjects

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

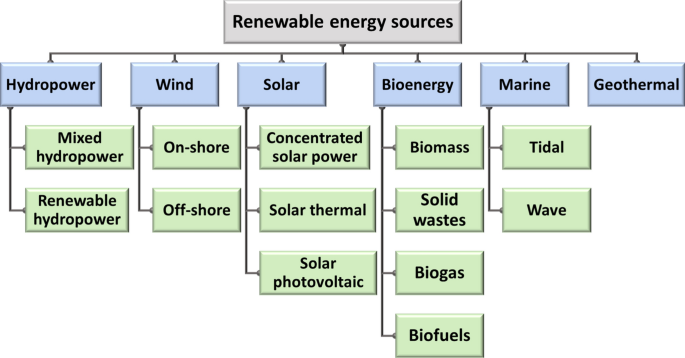

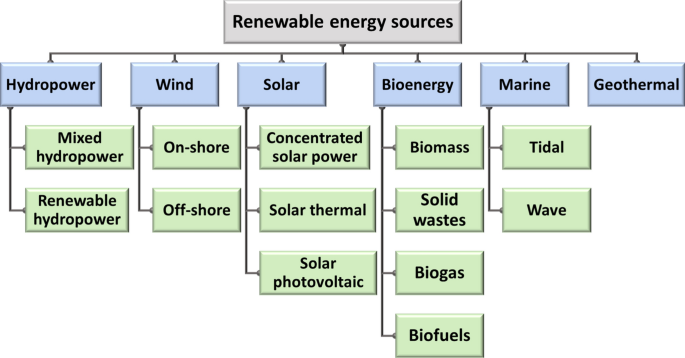

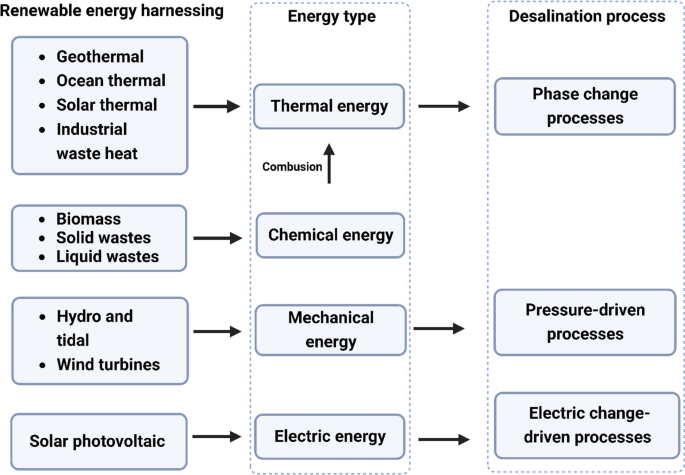

Hydrocarbons, specifically petroleum, coal, and natural gas, have been humanity's primary energy source for the past century. However, the ongoing threat of climate change and its effects on human health and well-being has dramatically increased the need for alternative energy sources. Hydrocarbons still account for over 80% of the world's energy supply. Furthermore, the production and use of fossil fuels are responsible for a significant portion (89%) of global greenhouse gas emissions, including carbon dioxide (Farghali et al. 2022). Additionally, reliance on imported fossil fuels risks energy security (Chen et al. 2022; Garba et al. 2021). To address these concerns, technologies based on renewable energy are crucial for achieving a sustainable energy future. As illustrated in Fig. 1, various forms of renewable energy have the potential to contribute to the global energy mix significantly. In line with this, there is a growing trend toward increasing the utilization of renewable energy sources, with projections suggesting that the share of renewable energy in global energy production will expand from 14 in 2018 to a projected 74% by 2050 (Osman et al. 2022). Globally, the power capacity of hybrid renewable energy increased from 700 to 3100 gigawatts between 2000 and 2021 (Rathod and Subramanian 2022).

Recent technological advancements in renewable energy systems have led to a reduction in both economic costs and environmental impacts. However, the intermittent nature of these resources remains a significant challenge in creating a reliable and long-lasting clean energy infrastructure. Integration between various sources is feasible and can increase system efficiency and supply balance, avoid limitations, and decrease carbon emissions. It is essential to evaluate the integration of renewable energy from both sustainability and technical perspectives, energy efficiency, and running costs. In addition, challenges to implementing a hybrid energy system must be addressed. This study explores the potential of combining various renewable energy sources and the associated environmental and social impacts. We examine the utilization of hybrid systems in water desalination and compare these systems' effects concerning their individual sources. Additionally, we consider the potential impact of climate change on the complementary operation of integrated systems and evaluate their flexibility in adapting to such changes. Furthermore, we examine the economic feasibility of renewable energy hybrid systems, including the estimation of costs and the potential for expansion in different countries.

Renewable energies hybridization and global production

Renewable energy systems can be based on a single source or a combination of multiple sources. A single-source system utilizes only one power generation option, such as wind, solar thermal, solar photovoltaic, hydro, biomass, and others, in combination with appropriate energy storage and electrical devices. On the other hand, a hybrid energy system combines energy storage and electrical appliances with two or more power generation options, including both renewable and non-renewable sources, such as diesel generators or small gas turbines (Sinha and Chandel 2014). Different configurations including photovoltaic–wind–diesel hydro–wind–photovoltaic, biomass–wind–photovoltaic, wind–photovoltaic, and photovoltaic–wind–hydrogen/fuel cell systems can be used in a hybrid energy system to generate electricity. Hybrid energy systems offer several advantages over single-source methods, such as increased reliability, decreased need for energy storage, and improved efficiency. However, a hybrid system can be oversized or improperly designed, leading to higher installation costs. Therefore, conducting thorough technical and financial analyses is essential when designing and implementing a hybrid energy system to utilize renewable energy sources effectively. Due to their complexity, hybrid systems require careful evaluation (Sinha and Chandel 2014).

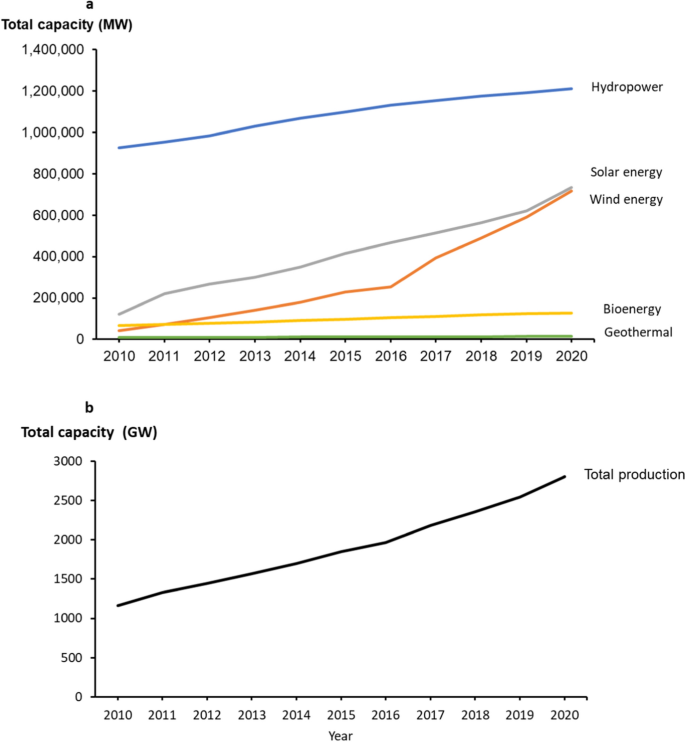

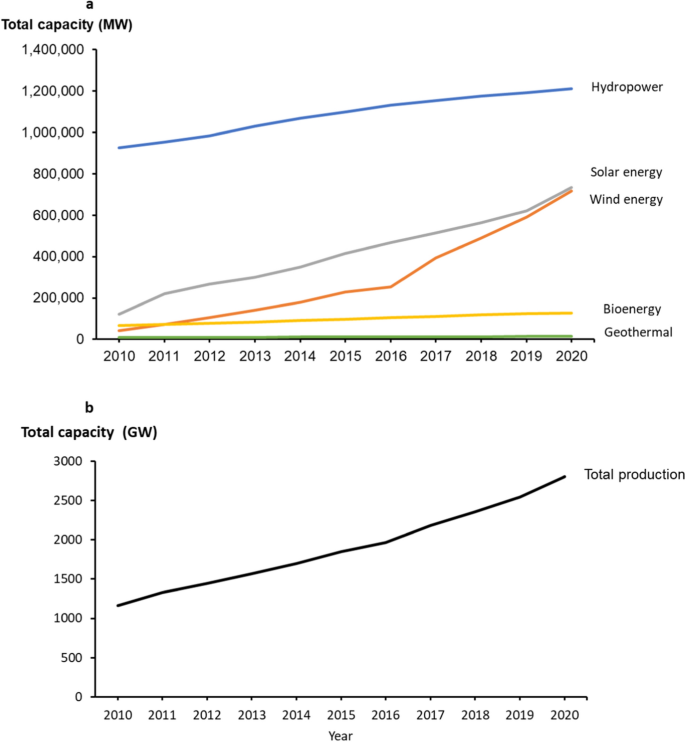

As of the end of 2020, there was a global total of 2799 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity available worldwide. The majority of this capacity, 43%, was from hydropower, with a capacity of 1211 gigawatts. Wind and solar energy comprised equal portions of the remaining capacity, with 733 gigawatts (26%) and 714 gigawatts (26%), respectively. The remaining 5% of energy came from other renewable energy sources, including 500 megawatts of marine energy, 127 gigawatts of bioenergy, and 14 gigawatts of geothermal energy (Al-Shetwi 2022; IRENA 2021). Figure 2 shows the significant increase in the proportion of renewable energy sources used in electricity generation from 2010 to 2020 (Al-Shetwi 2022; IRENA 2021).

A hybrid renewable energy system is created to overcome this challenge by combining different energy sources. These hybrid systems have the potential to surpass the capabilities of individual energy-producing technologies in terms of energy efficiency, economics, reliability, and flexibility. Globally, the power capacity of hybrid renewable energy systems increased from 700 to 3100 gigawatts between 2000 and 2021 (Rathod and Subramanian 2022).

Various factors influence renewable energy development, including climate change, global warming, energy security, cost reduction, and emission reduction (Osman et al. 2022). A study by Brodny et al. (2021) evaluated the level of renewable energy development in European Union member states and found that the energy revolution in Europe is progressing rapidly. The study found that between 2008 and 2013, the average gross electricity output from renewable energy sources in the European Union increased from 21.18 to 32.11%, and from 2013 to 2018, it reached 38.16%. This rapid shift toward renewable energy is expected to lead to the sustainable development of the economy and reduced emissions, in line with the European Green Deal concept. To achieve sustainable development, Tabrizian (2019) examined the role of technological innovation and the spread of renewable energy technologies in underdeveloped nations. The study found that renewable energy sources are the best and cleanest substitutes for fossil fuels and have a wide range of beneficial environmental consequences, including a significant decrease in greenhouse gas emissions, which is crucial given concerns about climate change. Green buildings may meet the needs of their residents by using renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, and geothermal energy while reducing their energy consumption and carbon footprint to zero (Chen et al. 2023). However, technology diffusion in this sector is slow, and renewable energy technologies are only gradually gaining traction in underdeveloped nations.

Similarly, Hache (2018) also noted that the spread of renewable energies would complicate global energy geopolitics and issues related to energy security. Therefore, the current increase in renewable energy installations must be considered alongside energy security and technological advancement for a smooth transition to renewable energy. The trend of renewable energy integration is expected to continue growing, with solar and wind power projected to account for 50% of global power generation by 2050 (Gielen et al. 2019).

Jacobson et al. (2017) found that 139 of the world's 195 nations have plans to transition to 80% and 100% renewable energy by 2030 and 2050, respectively. Additionally, many countries plan to use only renewable energy by 2050. A study by Zappa et al. (2019) shows that a 100% renewable energy power system would still require a significant flexible zero-carbon firm capacity to balance variable wind and photovoltaic generation and cover demand when wind and solar supply is low, even when wind and photovoltaic capacity is spatially optimized and electricity can be transmitted across a fully integrated European grid. Hydropower, concentrated solar power, geothermal, biomass, or seasonal storage are all potential sources of this capacity. Still, none of them are currently being used to the extent required to provide a 100% renewable energy system by 2050. The feasibility of a 100% renewable energy system in Europe by 2050 has been examined from various angles by Child et al. (2019) and Hansen et al. (2019). These studies indicate that renewable energy will continue to develop, and future developments in integration are anticipated.

Integrating renewable energy into the electrical power grid offers several benefits for the power and social, economic, and environmental sectors. From an environmental perspective, the electricity sector is currently a significant producer of carbon dioxide emissions (Bella et al. 2014). By 2040, energy-related emissions are predicted to increase by approximately 16% (Elum and Momodu 2017b). Therefore, electrical grids should be a crucial component of any effort to mitigate the worst effects of climate change and global warming. This is why low-carbon electricity generation that heavily relies on renewable energy sources is essential to a sustainable energy future as we progress toward deep decarbonization of the power industry (Bogdanov et al. 2021b). In this context, renewable energy can significantly support energy security and greenhouse gas reduction in the USA (Khoie et al. 2019). The use of fossil fuels and energy imports, the leading causes of carbon dioxide emissions in the USA, can also be reduced.

Additionally, according to Khan (2006), the increase in the integration of renewable energy into the utility grid has resulted in a reduction of approximately 527 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions from the electricity industry, as compared to the 46 million metric tons that were eliminated by renewable energy utilization in 2006. The recent renewable energy trend and its production growth will play a crucial role in the sustainable power sector's response to climate change and global warming. By switching to a 100% renewable energy supply, these sectors will reduce their carbon dioxide equivalent emissions by 90% by 2040, bringing them to zero in 2050 (Bogdanov et al. 2021a).

Environmental, social, and techno-economic impacts of hybrid renewable energy systems

Fossil fuel consumption is increasing dramatically due to excessive anthropogenic activities and industrial expansion to meet energy demands. The increase in fossil fuel consumption has risen by 96% since 1965 (Caglar et al. 2022), leading to adverse environmental impacts. Fossil fuels negatively impact air quality, the environment, health, and water resources. The gaseous emissions that can be released into the air due to fossil fuel consumption include greenhouse gases such as carbon oxides (carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide), sulfur oxides (sulfur dioxide and sulfur trioxide), nitrogen oxides (nitrous oxide and nitrogen dioxide), and volatile organic compounds and aerosols such as particulate matter. It was reported that about 72.5% of the global carbon dioxide equivalent emissions could be released from coal consumption (Sayed et al. 2021), causing the global warming phenomenon. The estimated gaseous emissions for various fossil fuels per megawatt-hour (MWh) of power generated are given in Table 1 (Turconi et al. 2013). One of every five deaths worldwide is induced by pollution from fossil fuel consumption (Azarpour et al. 2022). As a result of pollution, 350,000 people passed away in the USA in 2018. The annual cost of the health effects caused by fossil fuel consumption in the USA was reported to be 886.5 billion dollars (Azarpour et al. 2022). To mitigate the adverse impacts associated with fossil fuel consumption and achieve sustainability, the United Nations organization has established 17 goals for sustainable development (SDGs).

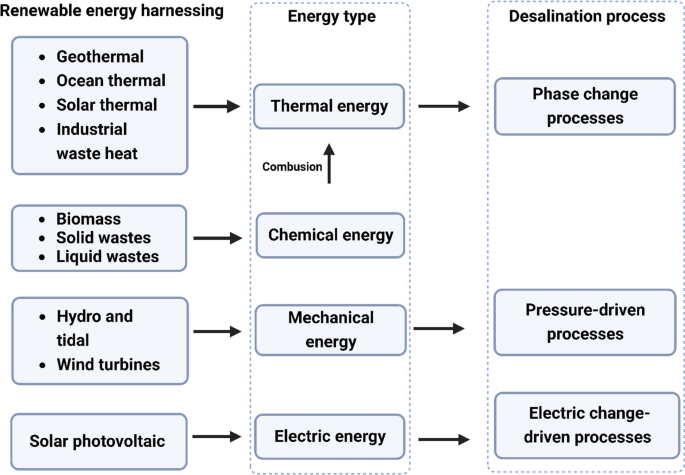

In comparison with a diesel system, a photovoltaic/wind/diesel/battery/convertor hybrid renewable energy system showed reduced rates of 60.7, 73.7, 62, and 81.5% in terms of the overall cost, renewable percentage, energy cost, and carbon dioxide emissions, respectively (Elmaadawy et al. 2020). A study showed that the photovoltaic/wind/battery storage hybrid renewable energy system supported by a diesel generator system is the most viable system for providing energy to the desalination unit in terms of economic and environmental benefits. It can reduce the cost of water production and adverse environmental effects by 69 and 90%, respectively, compared to other desalination units that rely on fossil fuels (Das et al. 2022b). To minimize the impacts of the water-energy nexus in India's coastal regions, the research examined an efficient desalination unit powered by renewable energy for the coastal villages of Tamil Nadu in India. The best option was a reverse osmosis desalination unit with a photovoltaic/wind/battery/diesel generator hybrid renewable energy system. The techno-economic and environmental analysis results showed that the lowest water cost is $4.57/m 3 , and the carbon dioxide generation is 2887 kg/year (Das et al. 2022b). The effectiveness of renewable options for water desalination, such as solar and wind, was examined. The study revealed that renewable energy sources could produce more energy at a lower cost, reducing the overall water desalination cost (Koroneos et al. 2007). Although using renewable energies in desalination plants is the most efficient approach for reducing carbon emissions, brine waste management must be considered to protect the environment and aquatic habitats.

Climate change and hybrid renewable energy

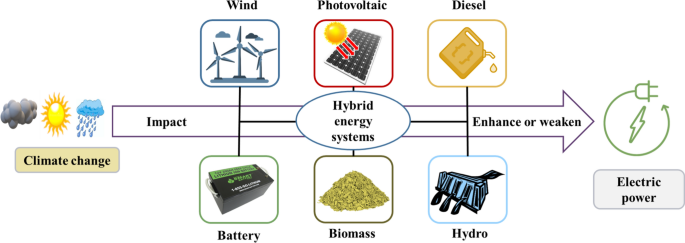

The majority of methods used to alter the climate of this planet involve entirely burning fossil fuels and cutting down trees. These methods include the human impact on the environment and temperature change. Global warming is mainly caused by climate change (Yoro and Daramola 2020). Burning fossil fuels releases many greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, significantly inducing global warming (Bhattacharjee et al. 2020). Global warming frequently causes natural disasters such as rising sea levels, hurricanes, severe droughts, increased flooding, heavy rainfall, and changes in the monsoon season (Bhattacharjee and Nandi 2020). As a result of changes in climatic parameters, such as river flow based on rainfall and photovoltaic power generation based on solar radiation, hybrid energy systems' resource sequences are also subject to change. Therefore, climate change makes these resources less stable (Milly et al. 2015), a significant obstacle for hybrid energy systems.

Impact of climate change on hybrid energy systems

Climate conditions vary depending on location (Mahesh and Sandhu 2015); hence, climate conditions are essential because the entire electricity generation system relies on them (Freitas et al. 2019). Moreover, energy flux is correlated with climate conditions and renewable energy endowment (Viviescas et al. 2019). For instance, solar energy is affected by daylight hours, unavailability at night, and rainy weather diminishes the intensity of light (Chwieduk 2018). In addition, changes in wind speed directly impact the electricity produced by hydroelectric systems, and seasonal droughts and excessive rainfall can also have an impact (Bhattacharjee and Nandi 2020; Ibrahim et al. 2022; Xiong et al. 2019).

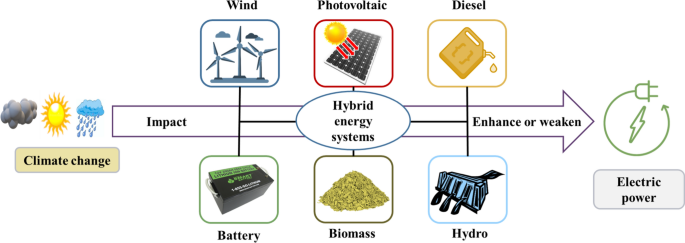

As a result, the development of hybrid energy systems enables it to reduce the adverse effects of climate change on the electricity system while ensuring supply stability, high power quality, and reliability, as well as decreased system efficiency unpredictability. The threat posed by climate change to renewable energy generation is significant, but renewable energy contributes significantly to the electricity grids of many countries (Elum and Momodu 2017a). Extreme climate conditions frequently occur, necessitating more flexible electrical systems to identify and isolate electrical faults and save maintenance costs (Kang et al. 2020). The impact of hybrid energy systems on climate change is demonstrated in Fig. 4 and Table 2.

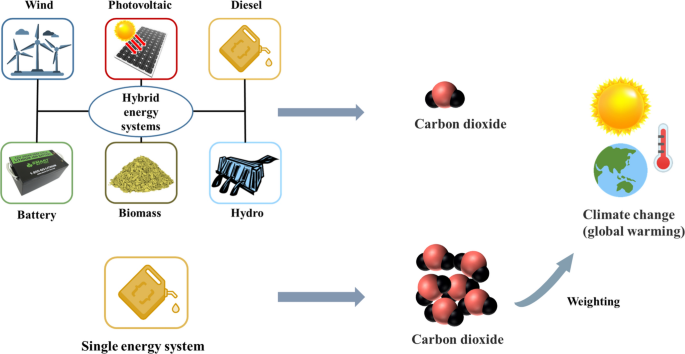

Distributed generation systems integration improves the carbon emissions of traditional centralized generation networks; for instance, Liu et al. (2018) simulated a 42% enhanced carbon reduction capacity of off-grid distributed photovoltaic/wind/diesel systems. However, such hybridization increases the average daily energy cost by 10%. Roy et al. (2020) found that innovative distributed hybrid systems applied to biomass/combustion batteries could reduce 1510 tons of carbon dioxide annually. The distributed generation approach markedly saves carbon dioxide emissions and reduces the potential for climate change from the generation system.

In conclusion, the hybrid energy system reduces the possibility of climate change impact and the proportion of greenhouse gases in the output by-product gases due to increasing renewables proportion. Therefore, the hybrid energy system contributes to lowering the carbon emission output of conventional energy sources and, therefore, is more sustainable. In contrast, distributed generation system is a novel power generation type that effectively improves the hybrid energy system's carbon footprint.

Climate change effects on the complementarity of hybrid energy systems

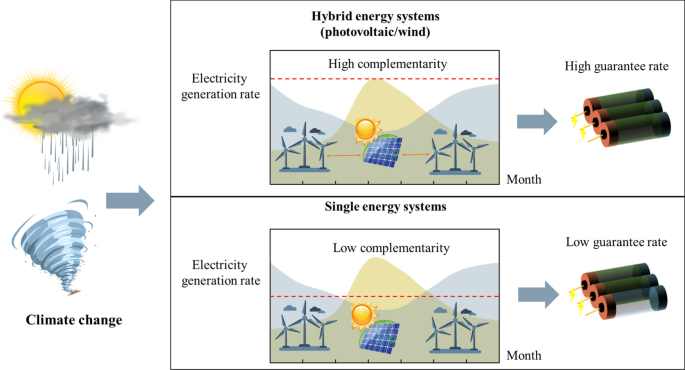

Hybrid energy systems' capacity to generate electricity is severely impacted by the unpredictability of the climate and weather, making hybridization more challenging to offer a secure and consistent power supply (Guezgouz et al. 2022; Lian et al. 2019). Climate variations in runoff rate, solar intensity, and wind speed can lead to uncertainty in complementary operations (Yan et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2020). Climate-dependent renewables such as wind, solar, and hydropower are mainly subject to uncertain natural conditions, which means there are challenges in providing a reliable and stable electricity supply (Wang et al. 2019a). The energy system's size, sensitivity, and adaptability all impact these uncertainties (Viviescas et al. 2019). Extreme weather events will become more frequent, severe, and prolonged due to climate change, and future climatic scenarios show how this may affect the stability of the world's electrical systems (Panteli and Mancarella 2015; Yang et al. 2022). However, this issue can be partially eased by merging complementary sources into a hybrid system and using the suggested dependable and economic dispatch approach. Hybrid renewable energy systems are more reliable than single energy systems (Abbes et al. 2014; Sawle et al. 2018), which is more advantageous in integrating multiple energy resources (Tezer et al. 2017). Jurasz et al. (2018) studied the complementarity of solar and wind energy, the impact on battery power, the need to reduce the potential for required energy storage, the impact on netload, or the change in complementarity due to climate change. The complementarity of resources can change the storage and system reliability of electricity. Wang et al. (2021) verified that the complementary photovoltaic/wind/hydroelectric energy model could obtain more stable and reliable power output than the single energy model.

Few studies have considered how hybrid energy systems will be impacted by climate change and evaluated how hybrid energy systems might work in tandem to adapt to climate change (Yang et al. 2022). However, this section outlines the parameters that have changed in relation to how the hybrid energy system's complementarity has changed due to climate change. Table 4 and Fig. 6 indicate that the hybrid energy system maintains a higher complementarity under strong climate change, and its complementarity meets the generation load demand.

The complementarity of numerous hybrid energy systems listed in Table 4 varies in response to climate change. The higher energy complementarity is observed compared to individual energy systems.

Rapid weather changes will somewhat impact the reliability of the power supply to the distribution network because renewable energy production is closely attached to meteorological conditions (Su et al. 2020). Jiang et al. (2021) measured the robustness of several hybrid photovoltaic/wind/hydroelectric energy types under different climatic conditions (water flow, photovoltaic power, and wind speed). The photovoltaic/wind/hydroelectric system was the most robust energy system to address climate change, resulting in a 4.90% increase in system power generation and a 37% guarantee. Moreover, the authors found that water flow is the largest factor affecting its performance efficiency. The likelihood of successfully satisfying stakeholder criteria through complementary manipulation is significantly higher than in a single operation. The complementary nature of photovoltaic and wind energy can be considered to increase the efficiency of power generation because the complementary manipulation reduces the impact of the penalty function setting in the system power output on the best choice. Yang et al. (2022) simulated and compared the energy complementarity of a photovoltaic/hydroelectric system under 961 different climate conditions data. The hybrid energy scenario adds 410 million kWh of annual electricity generation and a 63.14% guarantee rate, illustrating that hydropower and photovoltaic diminish the sensitivity to climate change impacts under complementary energy operating rules. On the other hand, the single energy system appears vulnerable (guarantee rate: 8.47%).

Hybrid photovoltaic/wind/hydroelectric power systems exhibit higher seasonal complementary energy benefits than separate operations from a single energy source (Tang et al. 2020). In particular, in autumn, the complementarity between energy sources was substantially improved (21.8% increase in the mutual coefficient) and proved that the interconnection of multiple energy sources guarantees year-round electricity and power quality throughout the day. Cheng et al. (2022) also studied complementary energy operations. They used remote sensing to predict energy operations under changing future climate scenarios. They found that complementary processes have higher power generation (5.46% increase) and higher reliability (5.13% increase) than single energy operations. Modern power systems now greatly emphasize the complementing process of hybrid power plants (Ming et al. 2018). In photovoltaic/wind/diesel systems, diesel fuel is only used as a backup energy source when solar and wind energy cannot satisfy load demand (Mandal et al. 2018). Diesel generator sets ensure the system's reliability under extreme climate conditions and enhance the system's economy (Liu et al. 2022). Li et al. (2019) investigated water/photovoltaic complementarity operations. Energy systems operating in a complementary manner can adapt to variable climates when runoff is constrained while being supplemented by generation at the photovoltaic output and increasing the guarantee of meeting urban load requirements by 10.39%. In addition, Puspitarini et al. (2020) found that the increase in flux caused by the accelerated rate of ice melting prompted by rising temperatures was 25% photovoltaic and 75% hydroelectric. Climate change has a significantly less impact on the complementarity of water and solar energy because of the increased sensitivity to changes in temperature and precipitation. Furthermore, elevation, glacier cover, and basin structure have uncertain effects. Higher energy complementarity is well demonstrated compared to individual energy systems.

However, the complementarity results depend on different methods, metrics, spatial and temporal resolutions, and data sample sizes (Canales et al. 2020; Kapica et al. 2021). Thus, complementarity analysis lacks a standard parameter and prevents researchers from comparing findings consistently (Yang et al. 2021). Additionally, there are more complex, multi-objective problems with complementary linked energy economics (Tang et al. 2020). As a result, it will be easier to plan, manage, and evaluate energy systems if diverse unpredictable inputs related to climate change are clearly defined. This will also help to inform sound decisions for planning and operating energy systems in a changing environment (Jiang et al. 2021). To reach the ideal system configuration, climatic modeling projections are used to assess the complementary energy efficiency of the area. Zhang et al. (2019) measured the weather forecast data to derive the optimal solution for the configuration of the photovoltaic/wind/hydrogen energy system, thus improving the system power reliability and selecting the optimal system configuration helps to avoid wasteful capital expenditures.

This section provides an overview of how a hybrid energy system performs in terms of energy efficiency under various climatic situations, which helps to identify the best energy configuration and provides greater climate stability than a single energy system. Hybrid energy systems are more advantageous in mitigating climate change, reducing the system's carbon emissions output. Moreover, complementary regulation between energy sources to adapt to climate change is more flexible and ensures efficient power production between energy sources.

Cost analysis

Economic parameters of the hybrid energy system

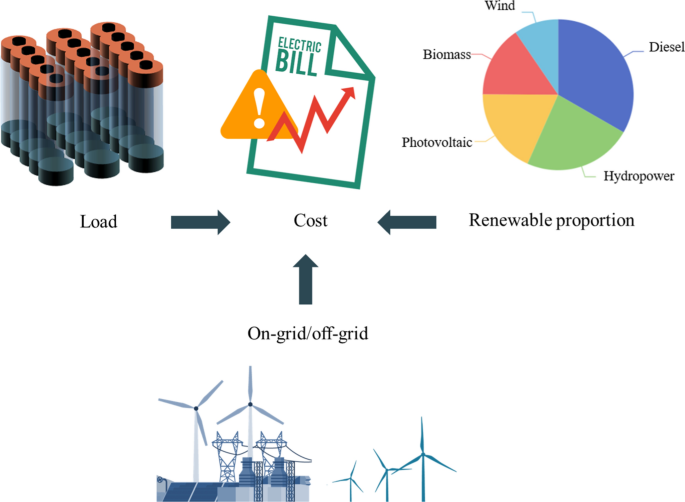

Increasing socioeconomic activity due to population growth necessitates a steady energy supply to keep up with demand (Olatomiwa et al. 2015). Satisfying everyday power needs through expensive conventional fuels is a huge challenge for the industry (Boamah 2020). For example, Nigeria's high cost of electricity and lack of reliability has crippled industrialization and national businesses (Adesanya and Pearce 2019; Osakwe 2018). Grid connection technology has made it possible to create electricity from renewable resources, and any surplus energy may be sold to the national grid (Ali et al. 2021a). Hybrid energy systems have the potential to address energy security, energy equity, and environmental sustainability (Pascasio et al. 2021). There is an urgent need for economically viable hybrid energy systems that meet the electrical load requirements of individual households and reduce local reliance on imported fossil fuels (Al-Turjman et al. 2020). Table 5 lists the essential indicators for the economic analysis of the energy system.

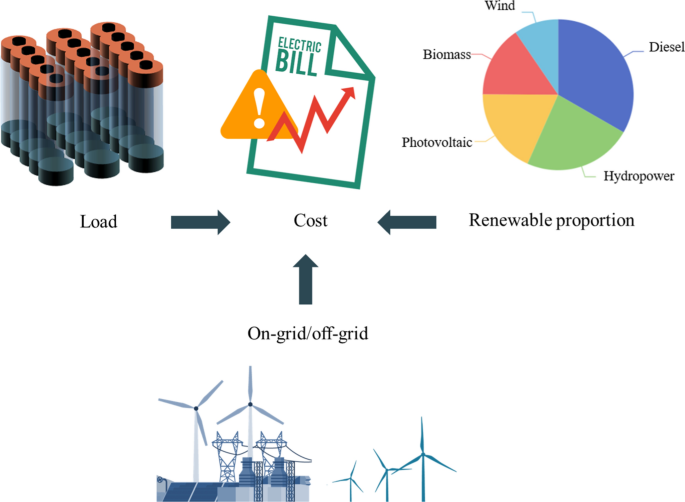

Unlike individual systems, load demand is a significant factor in developing hybrid renewable energy systems, which offer more dependable electricity for off-grid and stand-alone applications (Al-falahi et al. 2017). The load factor changes with energy demand and fixed costs are inversely correlated with peak load. Rajbongshi et al. (2017) examined the peak fixed load of the photovoltaic/biomass/diesel system. The authors found that the energy cost decreased from $0.145 to $0.119 as the load factor increased from 25 to 40%, so a higher load factor is needed to reduce the cost of electricity generation. Similarly, a solar/diesel/battery hybrid system was implemented in a rural Saharan community where load demand rose from 49.4 kWh/day to 89.4 kWh/day, causing a 33.35% decrease in photovoltaic penetration and a 31.6% reduction in energy cost (Fodhil et al. 2019).

The renewable proportion is the percentage of the system's overall energy production that comes from renewable energy sources and meets the load (Yuan et al. 2022). A high renewable energy percentage indicates a higher fraction of renewable energy in the load. To lessen the effects of environmental issues and to keep costs as low as possible, it is strongly advised to maintain a high share of renewable energy sources (Aziz et al. 2022). Increasing the renewable energy percentage reduces the net present value costs sustained by the system operator (He et al. 2023). However, it is necessary to comply with the government's energy policy by increasing the proportion of renewable energy sources with an appropriate renewable energy ratio and energy costs, reducing fuel and environmental pollution (Tsai et al. 2020). In this context, Pan et al. (2020) used a two-tier model to effectively lower the price of hydrogen supply at the planning stage by modifying the system's share of renewable energy equipment and sourcing power from an up-gradient site. However, large-scale use of renewable energy could threaten the power grid's security (Beyza and Yusta 2021), forcing the traditional distribution grid to move from employing a single power source to various renewable sources. This results in a tidal current reversal on the distribution grid, which changes the grid's power supply mode.

However, voltage distribution brings hidden risks to the distribution grid’s safe operation (Gong et al. 2021; Topić et al. 2015). Even with greater reserve capacity, consuming significant renewable energy is difficult due to transmission congestion and transmission section caps (Tan et al. 2021). As a result, integrating renewable energy into the power system is fraught with volatility and stochasticity, and the share of renewable energy increases stochasticity (Chen et al. 2021). Additionally, the proportion of renewable energy cannot be precisely controlled due to fuel uncertainty. However, by imposing a maximum proportion limit on each technology to keep fuel diversity within reasonable limits and maximum proportion constraint, the proportion of high-cost energy can be controlled to the maximum extent possible (Ioannou et al. 2019).

Costly renewable energy technologies necessitate expenditure (Toopshekan et al. 2020). Depending on the operation mode, adopting hybrid systems can boost overall dependability, lower power costs, or even raise the value of electricity (Esmaeilion 2020; Jurasz et al. 2020). In off-grid mode, capital, operation, maintenance costs, and grid tariff are the inputs for the economic comparison of off-grid systems and grid extensions. In an on-grid way, grid tariff and sell-back rate are the input data (Li et al. 2022). The advantage of being on-grid is that it sells excess clean energy to the grid and supports grid power, while the only source of revenue for being off-grid is salvage (Jahangir et al. 2022). Off-grid systems have higher net present costs and energy costs than grid-connected systems, whereas on-grid systems have fewer components because the primary power consumption is from the grid (Majdi et al. 2021; Nesamalar et al. 2021). On-grid hybrid is beneficial for reducing the cost of energy, but it takes time to set up and can lead to higher installation costs (Chowdhury et al. 2020). Das et al. (2021) conducted an economic feasibility analysis of a hybrid photovoltaic/wind/diesel/battery energy system. They found that the energy cost for an on-grid system (0.072 dollars/kilowatt-hour) was much lower than an off-grid hybrid energy system ($0.28/kWh). Additionally, Ali et al. (2021a) examined the economics of diesel and biogas generators, photovoltaic panels, and wind turbines in off-grid and on-grid scenarios. They found that on-grid systems with lower energy costs (0.072–0.078 dollars/kilowatt-hour) were more suitable for practical applications, with a 44–49% reduction over off-grid systems (0.145–0.167 dollars/kilowatt-hour).

In Guiyang, Li et al. (2021) studied green buildings, grid-connected systems were more cost-effective than off-grid systems for supplying electricity to residential buildings via hybrid intermittent generation systems. In off-grid systems, the battery capacity grows after the peak energy capacity surpasses the maximum electricity demand to prevent overproduction and avoid dumping extra power (Campana et al. 2019). Furthermore, Li et al. (2022) mentioned that increasing the capacity of photovoltaic panels, wind turbines, and converters allows flexibility and cost-effectiveness by shifting from off-grid to on-grid mode.

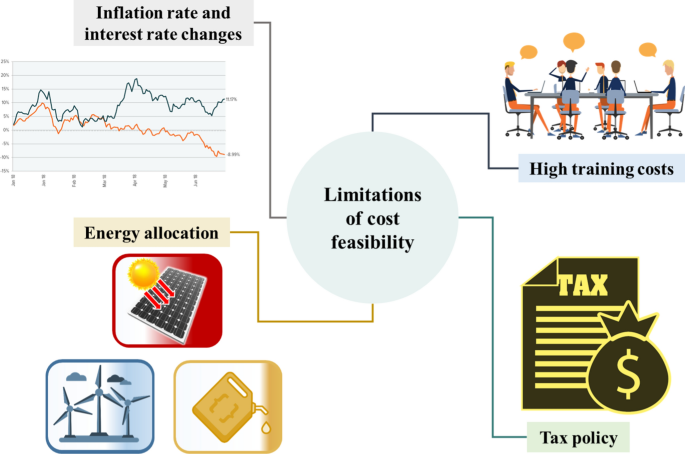

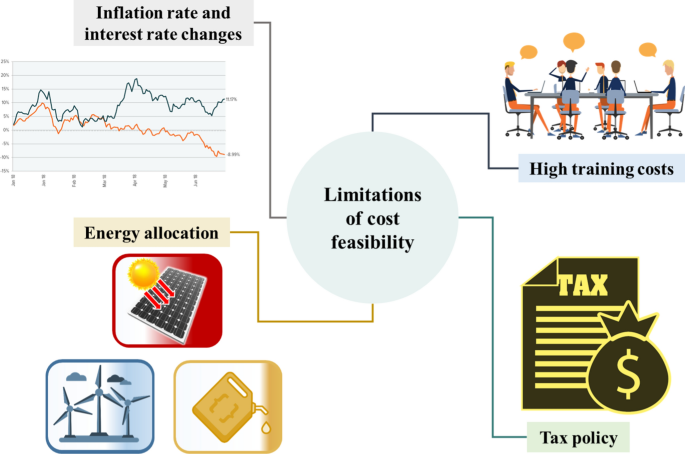

Most populations cannot afford high energy costs compared to traditional grid purchases. Hybrid energy systems pay much investment upfront due to the high renewable proportion, and the power transmission system still has higher costs. Therefore, it is essential to have a good electricity infrastructure to handle the transmission of these renewables (Das et al. 2020). Facing complex energy installation procedures also requires additional training costs (Ellabban et al. 2014). Photovoltaic prices can change significantly over time, and there is uncertainty in the prices of other energy sources, which good design decisions need to consider. Therefore, various decision variables between energy sources need to be considered in the optimization process to evaluate the optimal size of the hybrid system at the lowest annual cost (Sawle et al. 2018). Energy scheduling is based on previous-day simulations using predicted energy prices, weather data, and load consumption curves. Energy savings by scheduling energy use in houses connected to hybrid energy systems, energy scheduling strategy reduces daily operating costs by 45% (Bouakkaz et al. 2021). The developed procedure considers various constraints, such as the weight penalty cost of carbon emissions, the elemental cost of carbon dioxide, and the annual system component power consumption, to obtain the optimal configuration of the hybrid system (Clarke et al. 2015).

Similarly, inflation or nominal interest rates may vary over time (Das et al. 2022a; Shafiullah et al. 2021). Therefore, some economic policies have been implemented in favor of recommending hybrid energy applications (Xin-gang et al. 2020), for example, incentives in the form of tax exemptions and sales taxes on renewable energy imports of equipment in the UK (Ali et al. 2021b). The renewable energy policy in Bangladesh provides several fiscal incentives, such as a 15% value-added tax exemption on purchasing equipment and raw materials and a 10% increase in the purchase price for the private sector (Mandal et al. 2018). The availability of incentives or support programs through grants or subsidies can further address the high overall energy system costs by reducing investment costs (Odou et al. 2020). The current limitations of determining the economic viability of energy are summarized as shown in Fig. 8.

This section summarizes the economic parameters for evaluating hybrid energy systems, assessing net present cost, annualized cost, and cost of energy to provide a comprehensive analysis of the economic viability of hybrid energy systems. In addition, the hybrid energy system represents better economic viability than a single energy system. However, there is also the impact of renewable proportion and off-grid/on-grid operation mode; the system needs to address the challenges of high upfront investment cost, interest rate, and inflation rate resulting in price changes.

Conclusion

Estimating renewable energy hybrid impacts is essential to verify the future expansion of the hybridization concept compared to the individual used source. In addition, the economic estimation potential of such systems in different countries is essential. Here, we discuss the theory of renewable energy combinations, approaches, suggested combinations, models, and economic, environmental, and social impacts. The role of hybrid systems in water desalination was also included. Besides, a comparison between the effect of hybrid energy systems and their respective source was fully discussed to determine the best scenario for climate change mitigation. How the complementary operation of this integrated system could be affected by climate change and its flexibility to climate change was also discussed.

Complementarity between energy sources is improved when adapted to changing climate conditions, maximizing the ability to counteract its effects, and increasing power generation and guarantees. However, a standardized approach for evaluating energy complementarity is lacking, making it necessary to simulate complex climate data with more optimal estimation methods for accuracy.

Reducing the amount of non-renewable energy and increasing the proportion of renewable sources not only reduce net present value costs for system operators but also align with government energy policies and reduces fuel and environmental pollution. Yet, large or poorly designed systems can result in high installation costs, emphasizing the need for thorough technical and financial evaluations before implementing a hybrid energy system. Selecting the most valuable renewable source is vital for decision-makers in ensuring optimal utilization and successful implementation of such complex systems.

References

- Abba SI et al (2021) Emerging Harris Hawks Optimization based load demand forecasting and optimal sizing of stand-alone hybrid renewable energy systems– a case study of Kano and Abuja, Nigeria. Results in Engineering 12:100260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2021.100260ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Abbes D et al (2014) Life cycle cost, embodied energy and loss of power supply probability for the optimal design of hybrid power systems. Math Comput Simul 98:46–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matcom.2013.05.004ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Abdelhady S (2021) Performance and cost evaluation of solar dish power plant: sensitivity analysis of levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) and net present value (NPV). Renew Energy 168:332–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2020.12.074ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Aberilla JM et al (2020) Design and environmental sustainability assessment of small-scale off-grid energy systems for remote rural communities. Appl Energy 258:114004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.114004ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Abobakr A-T et al (2022) Wind and solar resources assessment techniques for wind-solar map development in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J Adv Res Fluid Mech Therm Sci 96(1):11–24. https://doi.org/10.37934/arfmts.96.1.1124ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Adefarati T et al (2021) Design and analysis of a photovoltaic-battery-methanol-diesel power system. Int Trans Electr Energy Syst 31(3):e12800. https://doi.org/10.1002/2050-7038.12800ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Adesanya AA, Pearce JM (2019) Economic viability of captive off-grid solar photovoltaic and diesel hybrid energy systems for the Nigerian private sector. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 114:109348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.109348ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Adeyemo AA, Amusan OT (2022) Modelling and multi-objective optimization of hybrid energy storage solution for photovoltaic powered off-grid net zero energy building. J Energy Storage 55:105273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2022.105273ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ahmed FE et al (2019) Solar powered desalination–technology, energy and future outlook. Desalination 453:54–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2018.12.002ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Ajlan A et al (2017) Assessment of environmental and economic perspectives for renewable-based hybrid power system in Yemen. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 75:559–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.11.024ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Al-falahi MDA et al (2017) A review on recent size optimization methodologies for standalone solar and wind hybrid renewable energy system. Energy Convers Manag 143:252–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2017.04.019ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Al-Ghussain L et al (2021) An integrated photovoltaic/wind/biomass and hybrid energy storage systems towards 100% renewable energy microgrids in university campuses. Sustain Energy Technol Assess 46:101273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2021.101273ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Al-Othman A et al (2022) Artificial intelligence and numerical models in hybrid renewable energy systems with fuel cells: advances and prospects. Energy Convers Manag 253:115154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2021.115154ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Al-Shamma’a AA et al (2020) Techno-economic assessment for energy transition from diesel-based to hybrid energy system-based off-grids in Saudi Arabia. Energy Transit 4(1):31–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41825-020-00021-2ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Al-Shetwi AQ (2022) Sustainable development of renewable energy integrated power sector: Trends, environmental impacts, and recent challenges. Sci Total Environ 822:153645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153645ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Al-Turjman F et al (2020) Feasibility analysis of solar photovoltaic-wind hybrid energy system for household applications. Comput Electr Eng 86:106743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2020.106743ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Alturki F, A, et al (2020) Techno-economic optimization of small-scale hybrid energy systems using manta ray foraging optimizer. Electronics 9(12):2045. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9122045ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Al Busaidi AS et al (2016) A review of optimum sizing of hybrid PV–Wind renewable energy systems in oman. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 53:185–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.08.039ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ali F et al (2021) A techno-economic assessment of hybrid energy systems in rural Pakistan. Energy 215:119103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.119103ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ali M et al (2021) Techno-economic assessment and sustainability impact of hybrid energy systems in Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. Energy Rep 7:2546–2562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2021.04.036ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Arvanitopoulos T, Agnolucci P (2020) The long-term effect of renewable electricity on employment in the United Kingdom. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 134:110322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2020.110322ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Awopone AK (2021) Feasibility analysis of off-grid hybrid energy system for rural electrification in Northern Ghana. Cogent Eng 8(1):1981523. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311916.2021.1981523ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Azarpour A et al (2022) Current status and future prospects of renewable and sustainable energy in North America: progress and challenges. Energy Convers Manag 269:115945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2022.115945ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Aziz AS et al (2019) Optimization and sensitivity analysis of standalone hybrid energy systems for rural electrification: a case study of Iraq. Renew Energy 138:775–792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.02.004ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Aziz AS et al (2022) A new optimization strategy for wind/diesel/battery hybrid energy system. Energy 239:122458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.122458ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Baneshi M, Hadianfard F (2016) Techno-economic feasibility of hybrid diesel/PV/wind/battery electricity generation systems for non-residential large electricity consumers under southern Iran climate conditions. Energy Convers Manag 127:233–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2016.09.008ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Barhoumi E et al (2020) Renewable energy resources and workforce case study Saudi Arabia: review and recommendations. J Therm Anal Calorim 141(1):221–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-019-09189-2ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Basu S et al (2021) Design and feasibility analysis of hydrogen based hybrid energy system: a case study. Int J Hydrog Energy 46(70):34574–34586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.08.036ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Bayer P et al (2013) Review on life cycle environmental effects of geothermal power generation. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 26:446–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2013.05.039ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bayrak F et al (2019) Effects of different fin parameters on temperature and efficiency for cooling of photovoltaic panels under natural convection. Sol Energy 188:484–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2019.06.036ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bella G et al (2014) The relationship among CO2 emissions, electricity power consumption and GDP in OECD countries. J Policy Modeling 36(6):970–985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2014.08.006ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Beyza J, Yusta JM (2021) The effects of the high penetration of renewable energies on the reliability and vulnerability of interconnected electric power systems. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 215:107881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2021.107881ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bhakta S, Mukherjee V (2017) Techno-economic viability analysis of fixed-tilt and two axis tracking stand-alone photovoltaic power system for Indian bio-climatic classification zones. J Ren Sustain Energy 9(1):015902. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4976119ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bhattacharjee S et al. (2020) Role of hybrid energy system in reducing effects of climate change. In: Qudrat-Ullah H, Asif M (eds.) Dynamics of energy, environment and economy: a sustainability perspective. Springer International Publishing, pp 115–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43578-3_6

- Bhattacharjee S, Nandi C (2020) Design of a smart energy management controller for hybrid energy system to promote clean energy. In: Bhoi AK et al (eds) Advances in greener energy technologies. Springer, Singapore, pp 527–563. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-4246-6_31ChapterGoogle Scholar

- Boamah F (2020) Desirable or debatable? putting Africa’s decentralised solar energy futures in context. Energy Res Soc Sci 62:101390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.101390ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bogdanov D et al (2021) Full energy sector transition towards 100% renewable energy supply: integrating power, heat, transport and industry sectors including desalination. Appl Energy 283:116273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.116273ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bogdanov D et al (2021b) Low-cost renewable electricity as the key driver of the global energy transition towards sustainability. Energy 227:120467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.120467ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bouakkaz A et al (2021) Efficient energy scheduling considering cost reduction and energy saving in hybrid energy system with energy storage. J Energy Storage 33:101887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2020.101887ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Brodny J et al (2021) Assessing the level of renewable energy development in the European Union Member States. A 10-year perspective. Energies 14(13):3765. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14133765

- Buenfil RV et al (2022) Comparative study on the cost of hybrid energy and energy storage systems in remote rural communities near Yucatan, Mexico. Appl Energy 308:118334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.118334ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Bundschuh J et al (2015) Low-cost low-enthalpy geothermal heat for freshwater production: innovative applications using thermal desalination processes. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 43:196–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.10.102ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Caglar AE et al (2022) Moving towards sustainable environmental development for BRICS: investigating the asymmetric effect of natural resources on CO2. Sustain Deve 30(5):1313–1325. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2318ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Campana PE et al (2019) Optimization and assessment of floating and floating-tracking PV systems integrated in on- and off-grid hybrid energy systems. Sol Energy 177:782–795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2018.11.045ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Canales FA et al (2020) Assessing temporal complementarity between three variable energy sources through correlation and compromise programming. Energy 192:116637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2019.116637ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Castro MT et al (2022) Techno-economic and financial analyses of hybrid renewable energy system microgrids in 634 Philippine off-grid islands: policy implications on public subsidies and private investments. Energy 257:124599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.124599ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Change PC (2018) Global warming of 1.5° C. World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland

- Chen H et al (2021) Multi-objective optimal scheduling of a microgrid with uncertainties of renewable power generation considering user satisfaction. Int J Electr Power Energy Syst 131:107142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2021.107142ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Chen L et al (2023) Green construction for low-carbon cities: a review. Environ Chem Lett. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-022-01544-4ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Chen L et al (2022) Strategies to achieve a carbon neutral society: a review. Environ Chem Lett 20(4):2277–2310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-022-01435-8ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Cheng Q et al (2022) Contribution of complementary operation in adapting to climate change impacts on a large-scale wind–solar–hydro system: a case study in the Yalong River Basin, China. Appl Energy 325:119809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.119809ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Child M et al (2019) Flexible electricity generation, grid exchange and storage for the transition to a 100% renewable energy system in Europe. Renew Energy 139:80–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.02.077ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Chowdhury T et al (2020) Developing and evaluating a stand-alone hybrid energy system for Rohingya refugee community in Bangladesh. Energy 191:116568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2019.116568ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Chwieduk D (2018) Impact of solar energy on the energy balance of attic rooms in high latitude countries. Appl Therm Eng 136:548–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2018.03.011ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Clarke DP et al (2015) Multi-objective optimisation of renewable hybrid energy systems with desalination. Energy 88:457–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2015.05.065ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Crawford RH (2009) Life cycle energy and greenhouse emissions analysis of wind turbines and the effect of size on energy yield. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 13(9):2653–2660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2009.07.008ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Cuesta M et al (2020) A critical analysis on hybrid renewable energy modeling tools: an emerging opportunity to include social indicators to optimise systems in small communities. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 122:109691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.109691ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Daniela-Abigail H-L et al (2022) Does recycling solar panels make this renewable resource sustainable? evidence supported by environmental, economic, and social dimensions. Sustain Cities Soc 77:103539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.103539ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Das BK et al (2019) Effects of battery technology and load scalability on stand-alone PV/ICE hybrid micro-grid system performance. Energy 168:57–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2018.11.033ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Das BK et al (2021) Feasibility and techno-economic analysis of stand-alone and grid-connected PV/wind/diesel/batt hybrid energy system: a case study. Energy Strateg Rev 37:100673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2021.100673ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Das BK et al (2017) A techno-economic feasibility of a stand-alone hybrid power generation for remote area application in Bangladesh. Energy 134:775–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2017.06.024ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Das HS et al (2020) Electric vehicles standards, charging infrastructure, and impact on grid integration: a technological review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 120:109618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.109618ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Das P et al (2022) Evaluating the prospect of utilizing excess energy and creating employments from a hybrid energy system meeting electricity and freshwater demands using multi-objective evolutionary algorithms. Energy 238:121860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.121860ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Das S et al (2022b) Techno-economic optimization of desalination process powered by renewable energy: a case study for a coastal village of southern India. Sustain Energy Technol Assess 51:101966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2022.101966Google Scholar

- Diemuodeke EO et al (2016) Multi-criteria assessment of hybrid renewable energy systems for Nigeria’s coastline communities. Energy Sustain Soc 6(1):26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13705-016-0092-xArticleGoogle Scholar

- Elkadeem M et al (2019a) Feasibility analysis and techno-economic design of grid-isolated hybrid renewable energy system for electrification of agriculture and irrigation area: a case study in Dongola, Sudan. Energy Convers Manag 196:1453–1478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2019.06.085ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Elkadeem MR et al (2019) Feasibility analysis and techno-economic design of grid-isolated hybrid renewable energy system for electrification of agriculture and irrigation area: a case study in Dongola, Sudan. Energy Convers Manag 196:1453–1478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2019.06.085ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ellabban O et al (2014) Renewable energy resources: current status, future prospects and their enabling technology. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 39:748–764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.07.113ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Elmaadawy K et al (2020) Optimal sizing and techno-enviro-economic feasibility assessment of large-scale reverse osmosis desalination powered with hybrid renewable energy sources. Energy Convers Manag 224:113377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2020.113377ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Eltawil MA et al. (2008) Renewable energy powered desalination systems: technologies and economics-state of the art. In: Twelfth international water technology conference, IWTC12

- Elum ZA, Momodu AS (2017) Climate change mitigation and renewable energy for sustainable development in Nigeria: a discourse approach. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 76:72–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.03.040ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Elum ZAA, Momodu AS (2017) Climate change mitigation and renewable energy for sustainable development in Nigeria: a discourse approach. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 76:72–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.03.040ArticleGoogle Scholar

- EnergyUR (2012) Water desalination using renewable energy. IRENA, Abu Dhabi

- Esmaeilion F (2020) Hybrid renewable energy systems for desalination. Appl Water Sci 10(3):84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-020-1168-5ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Farghali M et al (2022) Integration of biogas systems into a carbon zero and hydrogen economy: a review. Environ Chem Lett 20(5):2853–2927. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-022-01468-zArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Fawzy S et al (2020) Strategies for mitigation of climate change: a review. Environ Chem Lett 18(6):2069–2094. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-020-01059-wArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Fazelpour F et al (2016) Economic analysis of standalone hybrid energy systems for application in Tehran, Iran. Int J Hydrog Energy 41(19):7732–7743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.01.113ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Fodhil F et al (2019) Potential, optimization and sensitivity analysis of photovoltaic-diesel-battery hybrid energy system for rural electrification in Algeria. Energy 169:613–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2018.12.049ArticleGoogle Scholar

- François B et al (2018) Impact of climate change on combined solar and run-of-river power in Northern Italy. Energies 11(2):290. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11020290ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Freitas FF et al (2019) The Brazilian market of distributed biogas generation: overview, technological development and case study. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 101:146–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.11.007ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Galvan E et al (2020) Networked microgrids with roof-top solar PV and battery energy storage to improve distribution grids resilience to natural disasters. Int J Electr Power Energy Syst 123:106239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2020.106239ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Garba MD et al (2021) CO2 towards fuels: a review of catalytic conversion of carbon dioxide to hydrocarbons. J Environ Chem Eng 9(2):104756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2020.104756ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Gasparatos A et al (2017) Renewable energy and biodiversity: implications for transitioning to a green economy. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 70:161–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.08.030ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Gbadamosi SL et al (2022) Techno-economic evaluation of a hybrid energy system for an educational institution: a case study. Energies 15(15):5606. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15155606ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ghazi ZM et al (2022) An overview of water desalination systems integrated with renewable energy sources. Desalination 542:116063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2022.116063ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Ghenai C et al (2020) Technico-economic analysis of off grid solar PV/Fuel cell energy system for residential community in desert region. Int J Hydrog Energy 45(20):11460–11470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.05.110ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Gielen D et al (2019) Global energy transformation: a roadmap to 2050

- Goel S, Sharma R (2019) Optimal sizing of a biomass–biogas hybrid system for sustainable power supply to a commercial agricultural farm in northern Odisha, India. Environ Dev Sustain 21(5):2297–2319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-018-0135-xArticleGoogle Scholar

- Gökçek M, Kale C (2018) Optimal design of a hydrogen refuelling station (HRFS) powered by hybrid power system. Energy Convers Manag 161:215–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2018.02.007ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Gong X et al (2021) Renewable energy accommodation potential evaluation of distribution network: a hybrid decision-making framework under interval type-2 fuzzy environment. J Clean Prod 286:124918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124918ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Gude GG (2018) Renewable energy powered desalination handbook: application and thermodynamics. Butterworth-Heinemann Google Scholar

- Guezgouz M et al. (2022) Chapter 15 - Complementarity analysis of hybrid solar–wind power systems' operation. In: Jurasz J, Beluco A (eds.) Complementarity of variable renewable energy sources. Academic Press, pp 341–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-85527-3.00006-6

- Gunawardena KR et al (2017) Utilising green and bluespace to mitigate urban heat island intensity. Sci Total Environ 584–585:1040–1055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.158ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Hache E (2018) Do renewable energies improve energy security in the long run? Int Econ 156:127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inteco.2018.01.005ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Haghighat A et al (2016) Techno-economic feasibility of photovoltaic, wind, diesel and hybrid electrification systems for off-grid rural electrification in Colombia. Renew Energy 97:293–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2016.05.086ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hansen K et al (2019) Full energy system transition towards 100% renewable energy in Germany in 2050. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 102:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.11.038ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Haratian M et al (2018) A renewable energy solution for stand-alone power generation: a case study of KhshU Site-Iran. Renew Energy 125:926–935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2018.02.078ArticleGoogle Scholar

- He Y et al (2023) Hierarchical optimization of policy and design for standalone hybrid power systems considering lifecycle carbon reduction subsidy. Energy 262:125454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.125454ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ibrahim MM et al (2020) Performance analysis of a stand-alone hybrid energy system for desalination unit in Egypt. Energy Convers Manag 215:112941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2020.112941ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ibrahim NA et al (2022) Risk matrix approach of extreme temperature and precipitation for renewable energy systems in Malaysia. Energy 254:124471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.124471ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ioannou A et al (2019) Multi-stage stochastic optimization framework for power generation system planning integrating hybrid uncertainty modelling. Energy Econ 80:760–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2019.02.013ArticleGoogle Scholar

- IRENA (2021) Renewable Capacity Statistics 2021.https://www.irena.org/publications/2021/March/Renewable-Capacity-Statistics-2021

- Isa NM et al (2016) A techno-economic assessment of a combined heat and power photovoltaic/fuel cell/battery energy system in Malaysia hospital. Energy 112:75–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2016.06.056ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ismail MS et al (2015) Effective utilization of excess energy in standalone hybrid renewable energy systems for improving comfort ability and reducing cost of energy: a review and analysis. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 42:726–734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.10.051ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jacobson MZ et al (2017) 100% Clean and renewable wind, water, and sunlight all-sector energy roadmaps for 139 countries of the world. Joule 1(1):108–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2017.07.005ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jahangir MH, Cheraghi R (2020) Economic and environmental assessment of solar-wind-biomass hybrid renewable energy system supplying rural settlement load. Sustain Energy Technol Assess 42:100895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2020.100895ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jahangir MH et al (2022) Reducing carbon emissions of industrial large livestock farms using hybrid renewable energy systems. Renew Energy 189:52–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2022.02.022ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Javed K et al (2019) Design and performance analysis of a stand-alone PV system with hybrid energy storage for rural India. Electronics 8(9):952. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics8090952ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ji L et al (2022) Techno-economic feasibility analysis of optimally sized a biomass/PV/DG hybrid system under different operation modes in the remote area. Sustain Energy Technol Assess 52:102117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2022.102117Google Scholar

- Jiang J et al (2021) Hybrid generation of renewables increases the energy system’s robustness in a changing climate. J Clean Prod 324:129205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129205ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jurasz J et al (2018) The impact of complementarity on power supply reliability of small scale hybrid energy systems. Energy 161:737–743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2018.07.182ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jurasz J et al (2020) A review on the complementarity of renewable energy sources: concept, metrics, application and future research directions. Sol Energy 195:703–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2019.11.087ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kalinci Y (2015) Alternative energy scenarios for Bozcaada island, Turkey. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 45:468–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.02.001ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kalinci Y et al (2017) Energy and exergy analyses of a hybrid hydrogen energy system: a case study for Bozcaada. Int J Hydrog Energy 42(4):2492–2503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.02.048ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Kang J-N et al (2020) Energy systems for climate change mitigation: a systematic review. Appl Energy 263:114602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.114602ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kapica J et al (2021) Global atlas of solar and wind resources temporal complementarity. Energy Convers Manag 246:114692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2021.114692ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Karmaker AK et al (2018) Feasibility assessment & design of hybrid renewable energy based electric vehicle charging station in Bangladesh. Sustain Cities Soc 39:189–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2018.02.035ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Karmaker AK et al (2020) Exploration and corrective measures of greenhouse gas emission from fossil fuel power stations for Bangladesh. J Clean Prod 244:118645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118645ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kasaeian A et al (2019) Optimal design and technical analysis of a grid-connected hybrid photovoltaic/diesel/biogas under different economic conditions: a case study. Energy Convers Manag 198:111810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2019.111810ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kaur M et al (2020) Techno-economic analysis of photovoltaic-biomass-based microgrid system for reliable rural electrification. Int Trans Electr Energy Syst 30(5):e12347. https://doi.org/10.1002/2050-7038.12347ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Khan BH (2006) Non-conventional energy resources. Tata McGraw-Hill Education

- Khan FA et al (2018) Review of solar photovoltaic and wind hybrid energy systems for sizing strategies optimization techniques and cost analysis methodologies. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 92:937–947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.04.107ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Khan S et al (2022) Challenges and perspectives on innovative technologies for biofuel production and sustainable environmental management. Fuel 325:124845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2022.124845ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Khoie R et al (2019) Renewable resources of the northern half of the United States: potential for 100% renewable electricity. Clean Technol Environ Policy 21(9):1809–1827. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-019-01751-8ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Koroneos C et al (2007) Renewable energy driven desalination systems modelling. J Clean Prod 15(5):449–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2005.07.017ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lee J-Y et al (2019) Multi-objective optimisation of hybrid power systems under uncertainties. Energy 175:1271–1282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2019.03.141ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Li C et al (2021) Techno-economic and environmental evaluation of grid-connected and off-grid hybrid intermittent power generation systems: a case study of a mild humid subtropical climate zone in China. Energy 230:120728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.120728ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Li C et al (2018) Techno-economic comparative study of grid-connected PV power systems in five climate zones, China. Energy 165:1352–1369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2018.10.062ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Li F-F, Qiu J (2016) Multi-objective optimization for integrated hydro–photovoltaic power system. Appl Energy 167:377–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.09.018ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Li H et al (2019) Long-term complementary operation of a large-scale hydro-photovoltaic hybrid power plant using explicit stochastic optimization. Appl Energy 238:863–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.01.111ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Li J et al (2022) Optimal design of a hybrid renewable energy system with grid connection and comparison of techno-economic performances with an off-grid system: a case study of West China. Comput Chem Eng 159:107657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compchemeng.2022.107657ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Lian J et al (2019) A review on recent sizing methodologies of hybrid renewable energy systems. Energy Convers Manag 199:112027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2019.112027ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Liu H et al (2018) Sizing hybrid energy storage systems for distributed power systems under multi-time scales. Appl Sci 8(9):1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8091453ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Liu J et al (2020) Techno-economic design optimization of hybrid renewable energy applications for high-rise residential buildings. Energy Convers Manag 213:112868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2020.112868ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Liu Y et al (2022) Towards long-period operational reliability of independent microgrid: a risk-aware energy scheduling and stochastic optimization method. Energy 254:124291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.124291ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mahesh A, Sandhu KS (2015) Hybrid wind/photovoltaic energy system developments: critical review and findings. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 52:1135–1147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.08.008ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Majdi NN et al (2021) Case study of a hybrid wind and tidal turbines system with a microgrid for power supply to a remote off-grid community in New Zealand. Energies 14(12):3636. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14123636ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Malik P et al (2021a) Biomass-based gaseous fuel for hybrid renewable energy systems: an overview and future research opportunities. Int J Energy Res 45(3):3464–3494. https://doi.org/10.1002/er.6061ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Malik P et al (2021b) Techno-economic and environmental analysis of biomass-based hybrid energy systems: a case study of a Western Himalayan state in India. Sustain Energy Technol Assess 45:101189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2021.101189Google Scholar

- Mandal S et al (2018) Optimum sizing of a stand-alone hybrid energy system for rural electrification in Bangladesh. J Clean Prod 200:12–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.257ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Meng J et al (2022) Energy management strategy of hybrid energy system for a multi-lobes hybrid air vehicle. Energy 255:124539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2022.124539ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Merida GA et al (2021) The environmental and economic benefits of a hybrid hydropower energy recovery and solar energy system (PAT-PV), under varying energy demands in the agricultural sector. J Clean Prod 303:127078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127078ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Middelhoff E et al (2021) Hybrid concentrated solar biomass (HCSB) plant for electricity generation in Australia: design and evaluation of techno-economic and environmental performance. Energy Convers Manag 240:114244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2021.114244ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Milly PCD et al (2015) On critiques of “Stationarity is dead: Whither water management?” Water Resour Res 51(9):7785–7789. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015WR017408ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ming B et al (2018) Optimal daily generation scheduling of large hydro–photovoltaic hybrid power plants. Energy Convers Manag 171:528–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2018.06.001ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mohammadi MH et al (2021) Optimal design of a hybrid thermal-and membrane-based desalination unit based on renewable geothermal energy. Energy Convers Manag X 12:100124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecmx.2021.100124Google Scholar

- Mohammed OH et al (2019) Particle swarm optimization of a hybrid wind/tidal/PV/battery energy system. Application to a remote area in Bretagne, France. Energy Procedia 162:87–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2019.04.010ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Movahediyan Z, Askarzadeh A (2018) Multi-objective optimization framework of a photovoltaic-diesel generator hybrid energy system considering operating reserve. Sustain Cities Soc 41:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2018.05.002ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Nasser M et al (2022) Techno-economic assessment of clean hydrogen production and storage using hybrid renewable energy system of PV/Wind under different climatic conditions. Sustain Energy Technol Assess 52:102195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2022.102195ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Nawaz MH et al. (2018) Optimal economic analysis of hybrid off grid (standalone) energy system for provincial capitals of Pakistan : a comparative study based on simulated results using real-time data. In: 2018 International conference on power generation systems and renewable energy technologies (PGSRET)

- Nesamalar JJD et al (2021) Techno-economic analysis of both on-grid and off-grid hybrid energy system with sensitivity analysis for an educational institution. Energy Convers Manag 239:114188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2021.114188ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Odou ODT et al (2020) Hybrid off-grid renewable power system for sustainable rural electrification in Benin. Renew Energy 145:1266–1279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.06.032ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Oladigbolu JO et al (2021) Comparative study and sensitivity analysis of a standalone hybrid energy system for electrification of rural healthcare facility in Nigeria. Alex Eng J 60(6):5547–5565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2021.04.042ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Olatomiwa L et al (2015) Economic evaluation of hybrid energy systems for rural electrification in six geo-political zones of Nigeria. Renew Energy 83:435–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2015.04.057ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Osakwe PN (2018) Unlocking the potential of the power sector for industrialization and poverty alleviation in Nigeria. In: The service sector and economic development in Africa. Routledge, pp 159–180

- Osman AI et al (2022) Cost, environmental impact, and resilience of renewable energy under a changing climate: a review. Environ Chem Lett. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-022-01532-8ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Pan G et al (2020) Bi-level mixed-integer planning for electricity-hydrogen integrated energy system considering levelized cost of hydrogen. Appl Energy 270:115176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.115176ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Panteli M, Mancarella P (2015) Influence of extreme weather and climate change on the resilience of power systems: impacts and possible mitigation strategies. Electr Power Syst Res 127:259–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsr.2015.06.012ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Pascasio JDA et al (2021) Comparative assessment of solar photovoltaic-wind hybrid energy systems: a case for Philippine off-grid islands. Renew Energy 179:1589–1607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2021.07.093ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Pastore LM et al (2022) H2NG environmental-energy-economic effects in hybrid energy systems for building refurbishment in future national power to gas scenarios. Int J Hydrog Energy 47(21):11289–11301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.11.154ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Peddeeti S et al (2022) A case study in the identification of best combination of energy resources for hybrid power generation in rural communities through techno-economic assessment. Int J Ambient Energy. https://doi.org/10.1080/01430750.2022.2103183ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Peng X et al (2023) Recycling municipal, agricultural and industrial waste into energy, fertilizers, food and construction materials, and economic feasibility: a review. Environ Chem Lett. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-022-01551-5ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Perera ATD et al (2020) Quantifying the impacts of climate change and extreme climate events on energy systems. Nat Energy 5(2):150–159. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-020-0558-0ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Puspitarini HD et al (2020) The impact of glacier shrinkage on energy production from hydropower-solar complementarity in alpine river basins. Sci Total Environ 719:137488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137488ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Rabiee A et al (2021) Green hydrogen: a new flexibility source for security constrained scheduling of power systems with renewable energies. Int J Hydrog Energy 46(37):19270–19284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.03.080ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Rad MAV et al (2020) Techno-economic analysis of a hybrid power system based on the cost-effective hydrogen production method for rural electrification, a case study in Iran. Energy 190:116421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2019.116421ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Rahman A et al (2022) Environmental impact of renewable energy source based electrical power plants: solar, wind, hydroelectric, biomass, geothermal, tidal, ocean, and osmotic. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 161:112279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2022.112279ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Rajbongshi R et al (2017) Optimization of PV-biomass-diesel and grid base hybrid energy systems for rural electrification by using HOMER. Energy 126:461–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2017.03.056ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ram M et al (2020) Job creation during the global energy transition towards 100% renewable power system by 2050. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 151:119682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.06.008ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ramesh M, Saini RP (2020) Dispatch strategies based performance analysis of a hybrid renewable energy system for a remote rural area in India. J Clean Prod 259:120697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120697ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Rathod AA, Subramanian B (2022) Scrutiny of hybrid renewable energy systems for control, power management, optimization and sizing: challenges and future possibilities. Sustainability 14(24). https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416814

- Razmjoo A, Davarpanah A (2019) Developing various hybrid energy systems for residential application as an appropriate and reliable way to achieve Energy sustainability. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util Environ Eff 41(10):1180–1193. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2018.1544996ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Razmjoo A et al (2021) A Technical analysis investigating energy sustainability utilizing reliable renewable energy sources to reduce CO2 emissions in a high potential area. Renew Energy 164:46–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2020.09.042ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Razmjoo A et al (2019) Stand-alone hybrid energy systems for remote area power generation. Energy Rep 5:231–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2019.01.010ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Restrepo D et al (2018) Microgrid analysis using HOMER: a case study. DYNA 85:129–134. https://doi.org/10.15446/dyna.v85n207.69375ArticleGoogle Scholar